Inventing Crownring

Crownring began as a range extension on a completely different drive design—a flat reciprocating plate intended solely for the recumbent trike. A disability makes my riding an upright dangerous. But that same disability also allows my feet to fall from the pedals on a recumbent. The solution was to keep the pedals low by reciprocation, but that cut their ratio in half. Adding the bump at the greatest extension was to force that little bit more.

Applyng the bumps to a chainring was just a curiosity. I welded two rises to a steel 48T chainring, just bumps, and I took it for a spin in town. To my surprise I could feel no difference between the the top of the stroke at 48T and the bottom of the stroke at what turned out to be a 72T radius. Not only was I powering a 27 inch single speed bicycle with a 72/18 drive equivalent, but the stresses up the gentle hills in town were quite manageable. I immediately dropped work on the reciprocating trike a dove into what was at the time called the Speed Bump project.

That was my inspiration. The more I investigated the Speed Bumps the more complicated it became.

The first thing to know is how to determine the size of the bump. Wrap a chain around a chainring and slip it one tooth so the chain puckers. Slip it two teeth and it puckers more. Slip it three teeth and it's quite a large pucker.

By welding the bump to the 48T chainring, I had created what I later learned to identify as a 54T/48-72(3). It had a 54T draw, a 48T low radius (the original ring size), and a 72T high radius. The (3) means it puckered up three teeth.

Riding my bike in town was no problem on its flat streets and low grade hills. The bike was much faster with no noticeable increase in effort. Of course at home where hills are steep and plenty the 54T/48-72(3) was more of a chore than I could handle. But then, so was the original 48T. What ever magic that left 72T effortless in town went missing on the big hills.

I made a new Speed Bump chainring from a 46T. Without realizing it I'd made the bumps smaller. This little failure of attention led to one of my biggest understandings of the design. Bump size mattered.

The new ring was a 50T/46-59(2). 50T draw, 46T low radius, 59T high radius. even though the chain draw and the high radius exceeded the original 48T chainring, the 50T/46-59(2) was easier to power than the bike's original equipment. I came to find that starting the stroke with the low 46T radius was the reason for the ease of effort. Keeping the 46T through the greatest leverage prolonged its ease.

Basically, the first half of the stroke was a 46T chainring. Not until the second half of the stroke did the radius increase. But this increase did not hinder the hill climb. It in fact help to keep the speed up thus increasing kinetic energy.

My curiosity is insatiable. I needed to know why the 59T equivalent up the hill wasn't bogging me down. I set a stool beside a bathroom scale. As I sat I pushed on the scale with one foot. I managed 120 pounds at quite an effort. As my full weight of 200 pounds would be available during the second half of the stroke I was able to determine the second half of the stroke was getting 40% more strength than the first half of the stroke. 59T is only 28.26% higher than the 46T at the top. The rise in radius was well within the rise of strength. For that the 59T radius was no more difficult than the 46T radius. As the 59T kept the speed up, it made the following 46T radius that much easier. A 50T/46-59(2) Crownring is easier uphill than the standard 46T chainring because the 59T radius contributes to speed without noticeable effort. Of course that is uphill where every effort counts.

Taking the bike in town let me realize my 46T altered chainring was faster than the original 48T chainring. That seemed counter intuitive. Overwhelmed with curiosity again I dove into understanding why.

My first expectation was after realizing the altered 46T had a chain draw of 50T. Could a 50T be that much faster than a 48T? It didn't calculate out.

The bike came with 27 inch wheels, and a single-speed 48T/18 drive. That is enough information to calculate the distance of travel per stroke. The 27 inch wheel has a distance of 7 feet per rotation. The rotation of the wheel was calculated at 48/18=2.66. 7x2.66=18.62 feet per revolution, or 9.31 feet per stroke.

Using the same calculation, 50T draw is 9.72 feet per stroke. I confirmed this by measuring both rings for one stroke along a tape measure. Both calculations were accurate. The difference was not enough to account for the speed.

As I sat with the altered chainring in my hand, pretending stroke after stroke, I started to ponder the 59T radius. Even though the chain draw was 50T the 59T had to have some influence over the travel. If you push a pedal with a 59T radius, even if it is only for a small percentage of the stroke, wouldn't it still result in a 59T speed?

At this point I needed a way to compare what I then called the "crowned chainring" against the original equipment. I had the two like bikes. I need to ride one with original equipment and the other with a similar high radius. I had to make a crowned chainring with a 48T high radius.

Note: A crowned chainring in the bicycle industry is a chainring with sculpted teeth to improve shifting. After finding this information I changed crowned chairing to Crownring.

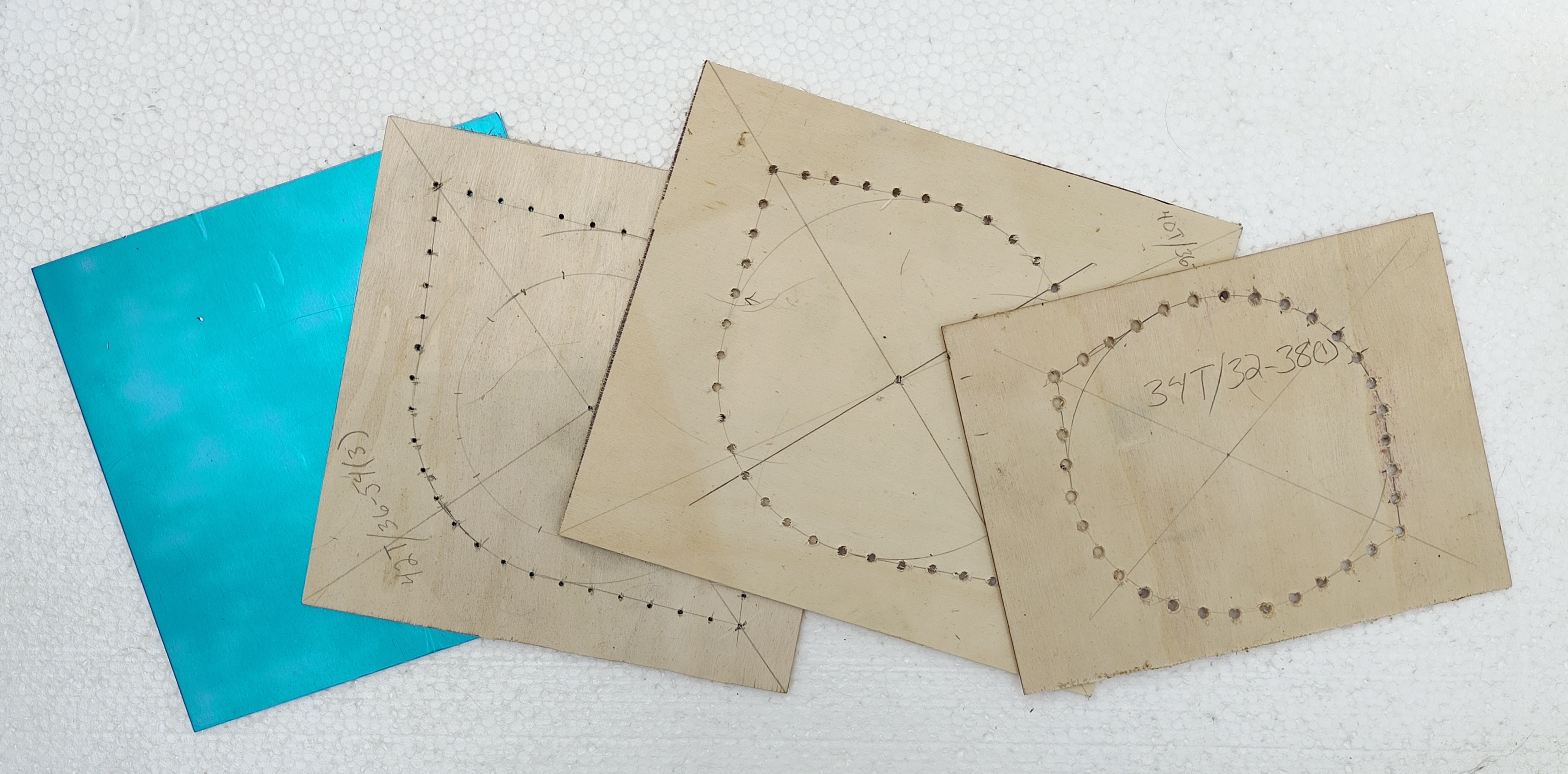

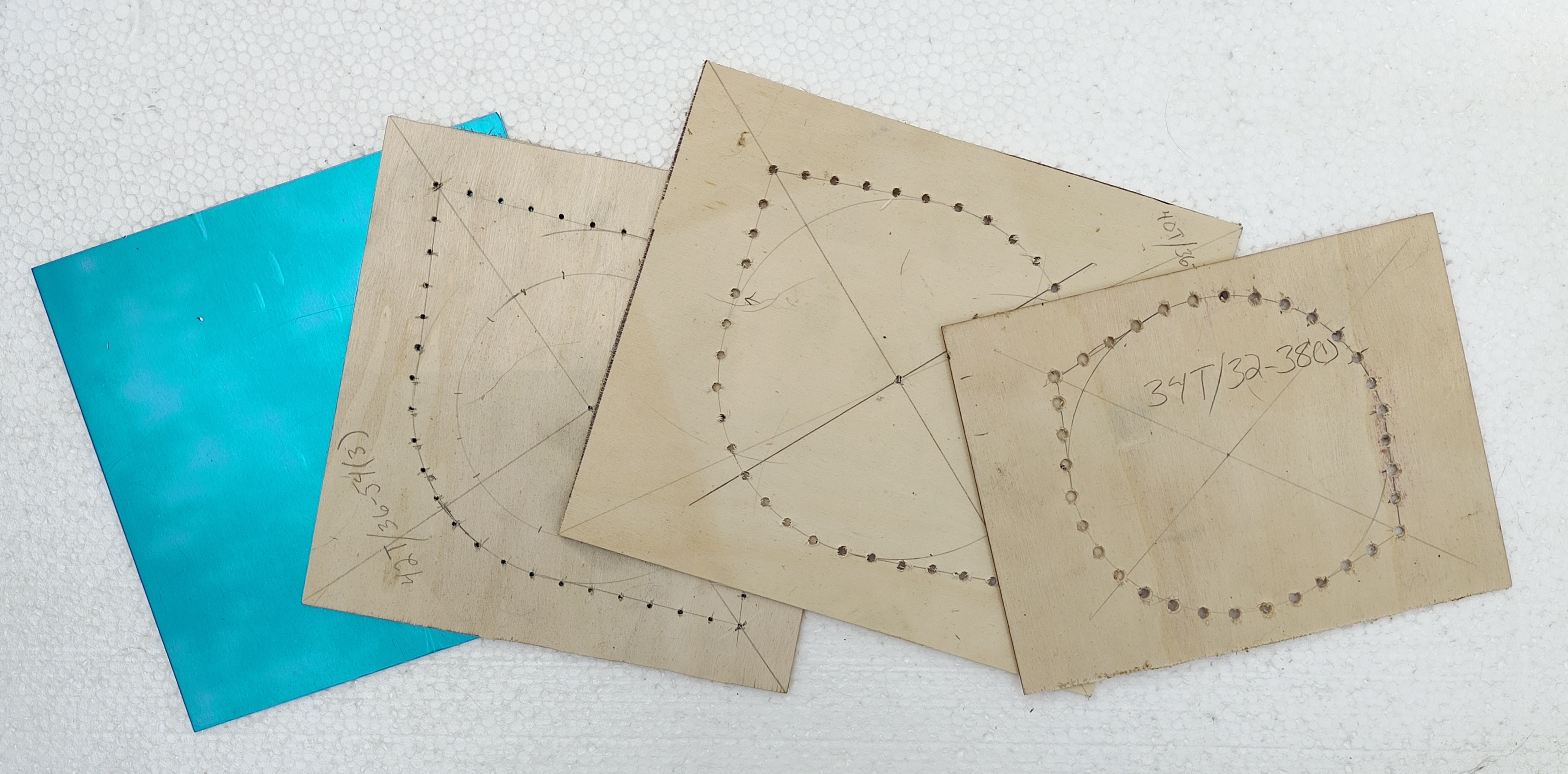

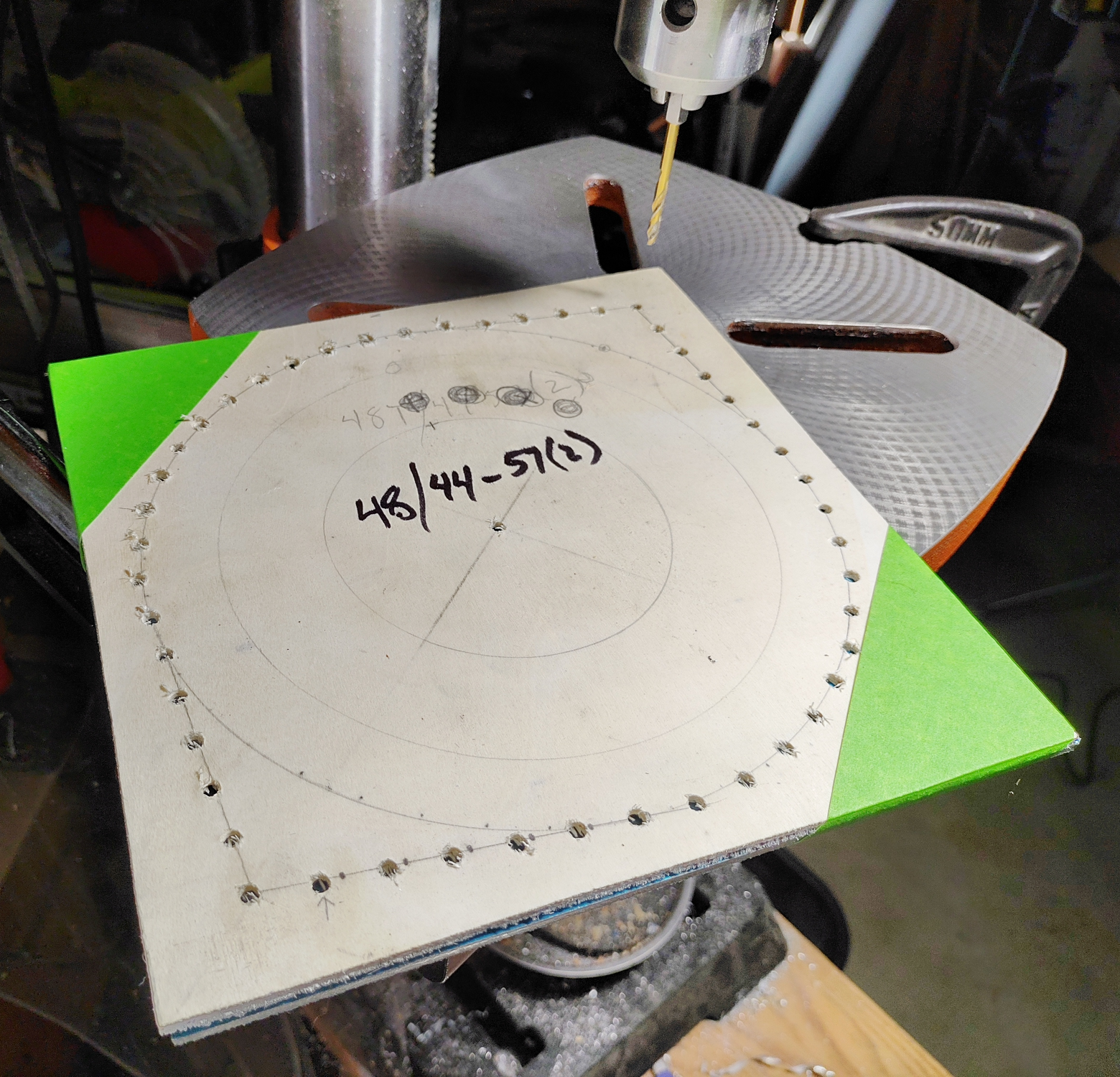

To test my hypothesis I needed to fabricate a Crownring from scratch. Before making the first full Crownring I made a wooden pattern. I couldn't get the teeth to count right. I struggled for days to work out why my two skip crown was giving me a 47 tooth ring and offset the placement of the crowns.

Once I'd drilled through the pattern and into the aluminum I could discard the pattern and work directly with the aluminum. To increase accuracy the pilot holes were much smaller than the chain links. They needed to be drilled to fit the links. Drilling one hole at a time using only a drill press took days to fabricate that first Crownring. Mistakes were made. Efforts to start over. Tweaks were designed. Eventually I had an imperfect but functional Crownring to compete directly with the 48T chainring.

I mounted the new Crownring onto the bicycle and went for a ride. It was smooth and comfortable. But was it as fast as the standard 48T bike?

I rode back to my shop and hopped onto the standard 48T control bike. Wow! I instantly noticed the extra effort I needed to power the 48T standard chainring. The control bike was not fun at all. I took it to speed but couldn't tell if one bike was faster than the other. I needed them to ride side by side.

I enlisted the help of my neighbor, Mike, and we rode the bikes together. I put Mike on the standard bike, what he was used to, and I rode the Crownring bike. Matching speed also matched cadence. The Crownring bike was indeed stroke for stroke equal to the control bike despite the difference in chain draw— one being 48 teeth and the Crownring being only 40 teeth.

After the initial ride we switched bikes. Mike's face lit up after his first stroke on the Crownring bike. "Smoooooth!" he exclaimed with a huge smile. We rode the bikes together with him tooling comfortably on the Crownring bike, and me struggling to keep up on the control bike.

That first demonstration of the Crownring confirmed without doubt that the Crownring bike lost no speed and was considerably easier to power.

As I rode the 40T/36-49(2), 40T(2) in shorthand, as I rode around the neighborhood tackling the intense hills the Crownring bike's performance far exceeded its sister bike, the 48T standard control bike.

The Crownring had been confirmed to excel in every aspect of performance.

My development of the Crownring has been a one man operation. My resources have been limited. Tentatively, the Crownring calculates out to more than 25% easier to power while delivering the same speed. I am eager to have this result challenged and the chance to empirically prove that Crownring is the most significant change to bicycling in the last 140 years.

It doesn't take a dynamometer to register the benefit of Crownring. Riding is believing. While Crownring won't benefit every challenge bicyclers tend to invent, for the majority of the wold's bicyclers Crownring will drastically improve their bicycling experience. More people will ride if their ride is not as stressful. The more that ride, the fewer that drive. Even if you've no concern of the climate, a Crownring is going to immensely improve both transportation and pleasure riding. Faster, easier. That's its physics. Who wants to work harder when they don't need to.

Text updated September 7, 2025

.png)